At Unite Europe this year, we at Unity released our public roadmap. And while it’s super cool to be able to share all of the amazing stuff we’re doing at Unity, one thing that is close to my heart is the Linux Editor.

The story behind Linux port of the Unity Editor is a lot like the story behind Linux runtime support, which was released in Unity 4.0. It’s basically a “Labor of Love”; some of us at Unity have been working off and on to port (and maintain the port) of the Unity Editor to Linux for quite some time (it’s pretty much the poster child of Unity’s internal developer hackweeks), and I must say, it’s coming along quite nicely. Our plan is to ship an experimental build Soon ™ to let you try it out.

Porting the editor to Linux is a lot of work — much more work than porting our runtime. This is because the editor is where the majority of our actual tech lies (including most of our complex 3rd-party integrations) and because of the asset database, it’s the place where case sensitivity problems really show up. Our editor consists of:

- A lot of C++ code, much, but certainly not all, of which is shared by the runtime; this is of course compiled natively.

- A lot of C# code, which runs on top of Mono.

- Various 3rd-party libraries and middleware, all of which must be compiled for Linux.

Now that we are this far along, let’s look back on a few big things Na’Tosha “wishes we’d done then”…

1. Cared About Case Sensitivity

Unity does not properly run on a case-sensitive file system (which is something that Unity users have discovered if they’ve tried to install and run Unity on a case-sensitive HFS+ file system). This is primarily due to Unity’s asset database, and how it stores paths to map them to GUID values. Of course we tried to be smart in the early days, but if you don’t set up a way to actually verify that what you’re doing works on a case-sensitive file system, then it will never fail that some well-intentioned programmer throws a toLower() in somewhere and ruins the party.

This is definitely something I wish we’d cared about in the past because fixing it after-the-fact is difficult and tedious.

2. Didn’t #if WINDOWS #else OSX

A non-trivial amount of our early work porting the Editor to Linux involved dealing with stuff like:

#ifdef WIN32 return _isnan(val) != 0; #elif __APPLE_CC__ return std::isnan(val) != 0; #endif

Or alternatively:

#if UNITY_WIN // Some Windows-specific codepath #else // Some Mac-specific codepath #endif

le sigh.

Conclusion: If you want to write portable code, always do something sane (read: future-proof) in the #else case.

3. Just Didn’t Assume

The above-two points are the big ones. A few other, smaller, things include:

- Assumptions about compilers. An example is our bug reporter in Unity 5, which is in many ways separate from the main editor and is written using some C++11 features. The C++11 standard is, ahem, vague in some places and different compilers choose to interpret the standard, well, differently. This makes porting something using C++11 to a 3rd compiler a pain. Lots of compilation errors that involve this-c++-template-thingy-with-lots-of-angle-brackets does not match that-c++-template-thingy-with-lots-of-angle-brackets-that-has-a-const-somewhere-in-the-middle.

- Assumptions about native applications. This includes what sort of stuff goes in the application menus automatically (on Windows, for example, you get some stuff added to the application menu for free (Copy/Paste/etc)). We had to go through and add this stuff in for Linux, because GTK applications don’t get these for free. To be fair, most of this stuff doesn’t come ‘for free’ on OS X, either, but the way it was implemented falls into the #if WINDOWS #else OSX trap I wrote about above.

- Assumptions about how file dialogs work. Other platforms have callback systems, for example, so the parent application can tell the dialog if something should or should not be select-able. The default GTK widgets don’t work this way.

- Assumptions in general. Conclusion: assumptions really are the root of all evil. 🙂

All that being said, the project has definitely been a lot of fun, hindsight is always 20/20, and these are actually the kind of problems I’d expect anywhere when porting a codebase the size and complexity of Unity to a new platform.

Just for fun, I’ll also mention that throughout the porting process, we’ve gone back to the drawing board on a couple of things:

- The first pass used raw X11 for windowing/event handling because we were trying to avoid a dependency on either GTK or QT.

- Because of (1) the early menu system was actually a menu system written in Unity GUI. I still think this would be pretty cool if we did it someday.

- In Unity 5.1, CEF was embedded as the embedded browser system, and this had a dependency on GTK, so we switched to GTK for window/event handling and for the menu system.

But other than this, we haven’t really had to do any re-work.

So what how is the Editor going to work? Here’s what we know:

- Only 64-bit Linux will be supported

- Same policy as with our runtime; in order to keep our own sanity, we will officially support Ubuntu Linux. Other distributions are on their own, but it will probably work other places.

- We’ll most likely support back to Ubuntu version 12.04 (it’s what we’re building on in our build farm currently)

- Features reliant on 3rd party stuff (e.g, Global Illumination) should work

- Installer will (most likely — it’s one of the things we didn’t do yet) just be a .deb package.

- Some of the model importers that rely on external applications (i.e, 3ds Max and SketchUp) won’t work. The workaround is to export to FBX instead.

Anyway, that’s it for now.

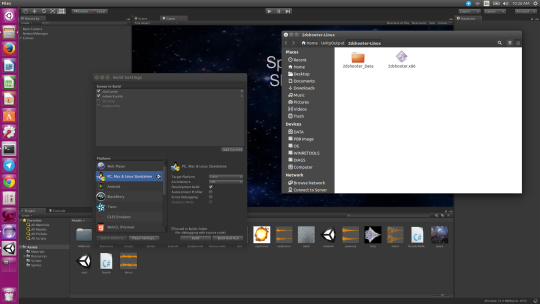

Here’s a teaser:

Our Networking demo 2d Shooter being exported to Linux from inside the Linux Editor.

Unity Labs running in the Linux editor. It’s running here on a Retina MacBook Pro, which is why the fonts are small.

Are you excited about the Unity Editor on Linux? What are you going to use it for? What platforms do you want to export to from Linux? Tweet me at @natosha_bard and tell me what you’ll do with it!